Matthew 18:21-35

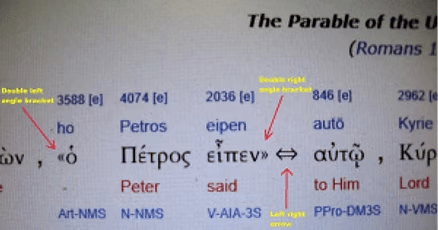

“Peter came and said to Jesus, “Lord, if another member of the church sins against me, how often should I forgive? As many as seven times?” Jesus said to him, “Not seven times, but, I tell you, seventy-seven times.

“For this reason the kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who wished to settle accounts with his slaves. When he began the reckoning, one who owed him ten thousand talents was brought to him; and, as he could not pay, his lord ordered him to be sold, together with his wife and children and all his possessions, and payment to be made. So the slave fell on his knees before him, saying, ‘Have patience with me, and I will pay you everything.’ And out of pity for him, the lord of that slave released him and forgave him the debt. But that same slave, as he went out, came upon one of his fellow slaves who owed him a hundred denarii; and seizing him by the throat, he said, ‘Pay what you owe.’ Then his fellow slave fell down and pleaded with him, ‘Have patience with me, and I will pay you.’ But he refused; then he went and threw him into prison until he would pay the debt. When his fellow slaves saw what had happened, they were greatly distressed, and they went and reported to their lord all that had taken place. Then his lord summoned him and said to him, ‘You wicked slave! I forgave you all that debt because you pleaded with me. Should you not have had mercy on your fellow slave, as I had mercy on you?’ And in anger his lord handed him over to be tortured until he would pay his entire debt. So my heavenly Father will also do to every one of you, if you do not forgive your brother or sister from your heart.”’

—————————————————————————————————–

This is the Gospel reading for Year A Proper 19, the fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost. It will next be read aloud by a priest on Sunday, September 17, 2017. This lesson is important because it addresses the issue of forgiveness by human beings, with the parable of the Unmerciful Servant told.

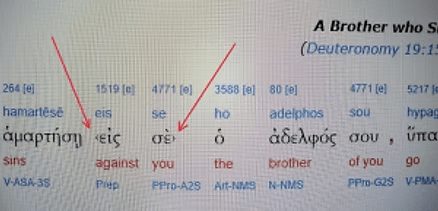

The context of this reading is it continues Matthew’s account of the Proper 18 lesson, when Jesus explained to his disciples (as a Sabbath clarification of a reading from the scrolls from Deuteronomy) how it was the responsibility of each follower to maintain the religious focus of other followers. That began by one confronting another who had sinned against that one. Having personally witnessed a breaking of the laws, each of God’s devoted faithful was required to bring such an offender to honest repentance.

When this reading begins by Peter asking Jesus a question about forgiveness limits, it does not mean that he rose in a synagogue and challenged Jesus’ instruction of how a Law of Moses should be applied to modern believers (then and now). It makes more sense that Peter had contemplated what Jesus said and later spoke outside the synagogue, when only Jesus and the disciples were present. Therefore, it should be noted that the Proper 18 Gospel focus was not on forgiveness, but the responsibility of confronting sinners; and Jesus was doing his share of pointing out how the Pharisees and priests of the Temple were in a confrontational state with little repentance openly stated by anyone.

Peter, who appears often as the spokesman of the disciples, was then asking Jesus when confrontation should end and complete separation begins, as far as keeping the “Church” pure. Because the Law forbid Jews from commonly associating with Gentiles (and the disciples were not yet Apostles), they could understand Jesus’ instruction to directly confront one on one, then confront in a small group, before advancing to confrontation before the whole gathering in the synagogue.

In general, all Gentiles were sinners, so there was no need to forgive them for not being born into the exclusive race-religion that bore the responsibility of being chosen by God. Thus, Peter’s question was about who excommunicates who among Jews and when? This was relative to one who had run the gamut of confrontations, but who (still was born Jewish) was just not feeling any responsibility to obey the laws of Moses.

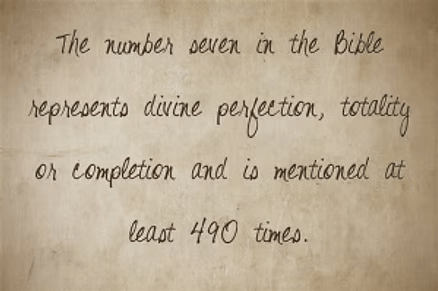

For Peter to ask Jesus, “Lord, if another member of the church sins against me, how often should I forgive? As many as seven times?” it is important to realize that Peter did not just pick the number seven out of thin air. Seven is a special number, which is repeated in Biblical stories that include cycles of seven weeks and seven years, but the greatest aspect to grasp is seven days. The seventh day is the Sabbath, which God blessed as holy and rested from His work of Creation. Therefore, Peter was asking if devoted Jews should rest all complaints against those who simply would not comply with Law, and allow them to act unrepentant by simply being Jewish … God’s chosen people (remnants thereof).

When we then read: “Jesus said to him, “Not seven times, but, I tell you, seventy-seven times.”’ This has to be realized as Jesus saying, “Seven times eleven times.” This, like the number seven, is also use of numbers to symbolically make an important statement. This is because the number eleven is a holy number.

In Numerology (a division of Kabbalistic training that teaches how to recognize signs and symbols), there are nine base numbers: 1 through 9. A ten is a repeated 1, as 10=1+0 => 1. All numbers can be reduced to one of the base numbers, no matter how large the number. For example, 2017 is seen as 2+0+1+7=10 => 1+0=1. A 1 number symbolizes the beginning of a cycle; so the year 2017 is (generally) symbolic of a year starting a new cycle [such as a new President and new reaction to him … for one of many possible examples].

Still, besides the base numbers, Numerology recognizes three Master Numbers: 11, 22, and 33. Each of those numbers represents elevations from the mundane or base, due to holiness levels achieved. An 11 could be a base 2, with a 22 elevated from 4 and 33 a higher form of 6, with the difference being the presence of God in some way. As such, it is easy to reflect a 2, but it takes a special presence to reflect that as an 11.

The number 2 is a reflection of duality. A base 2, as seen in Peter’s question, is 1 relating to another 1, where 2 are the focus. Peter’s focus on how he (1) should deal with someone (1) who sins against him is an ordinary circumstance of relationship. For Peter to use the number 7 as how he (1) should accept the sins of another (1), he sought a peaceful solution that reflected forgiveness because “God said to rest.” It removed God from 2, where 1 acts as God says, and another 1 does not act that way.

Jesus said, “No!” to that common (human) response to another’s sin. Jesus said, “Let God be the influence for forgiveness.” This means Jesus said not to be 1+1=2 but be 1+10=11, where that number becomes 1+God (10). One’s self is then elevated intuitively, from the common and mundane, to a spiritual presence of God incarnate in 1. Thus, to act in a restful and holy way to the presence of sin in another, one should do more than react to what was being told by God through Moses. Instead, act by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit within. That is the true answer Jesus gave to Peter’s question.

Of course, neither Peter nor the other disciples (remember, Judas Iscariot is still present with the disciples then, and possibly Peter has witnessed Judas stealing – a sin against them all) were elevated as 11’s yet (much less 22’s or 33’s). They still stumbled around as 2’s, 4’s, and 6’s, so what Jesus said often flew over their human brains. While they would later full well recall this lesson and understand its meaning (after being filled with the Holy Spirit), they needed to hear Jesus tell a parable that would make everything about the 7×11=77 be more meaningful later.

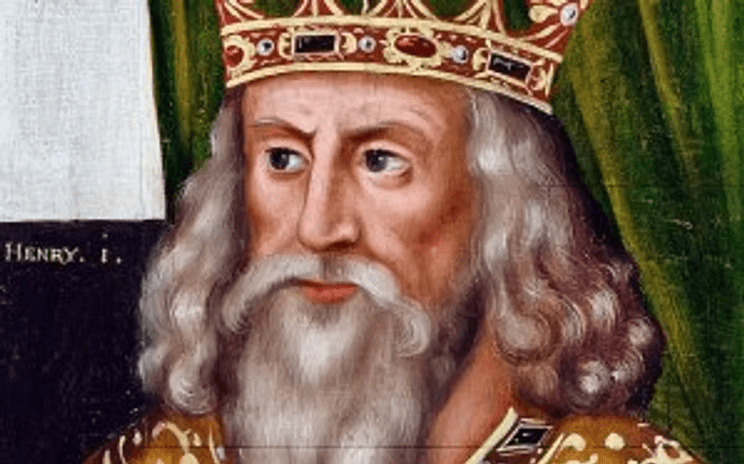

Realizing this aspect of numerological values, the parable begins by saying, “For this reason the kingdom of heaven may be compared to a king who wished to settle accounts with his slaves.” This is relative to the number seventy-seven (or seventy times [and] seven). The “kingdom of heaven” is brought to earth by God’s presence in one who does as Jesus says about how many times to forgive a sinner. Therefore, a king (more like an emperor) is reflective of the number seventy-seven, as an eleven times seven, such that an Apostle is the kingdom in which God presides.

The slaves are each a one, just like the person was (like Peter) who wanted to “settle accounts” before he was elevated to that kingly status. While Jesus referred to God as the landowner or king in other parables, it is best to see the king (11 x 7) here as a human being (1) influenced by God (10). After all, we are all humans first.

One needs to also see the parable addressing Peter, who along with the other disciples would become kings after the Holy Spirit lit upon them. Without that holy presence, the king of the parable would simply be someone like a Pharisee (a wealthy landowner with slaves), who would not otherwise “wish to settle accounts with his slaves.” That “desire” (an alternative translation for “ēthelēsen”) comes from an elevation from common human (one of Jewish race-religion) to one who wants to do the right thing and do as Jesus said (“forgive as a seventy-seven”). The title of king (“basilei,” which infers emperor) means one of great wealth, but material possessions (money and property) should be interpreted as side-effects of God’s blessings. Thus, the king gave his blessings to his slaves. The measure in “talents” (as the symbolism of the parable of the talents) is more powerful when viewed as the gifts of the Holy Spirit.

The focus that then goes to “one who owed [the king] ten thousand talents,” who “was brought to [the king]” for repayment, should be seen as the type of person that spurred Peter’s question about how much should I give, with never any repayment. To see just how much value was placed upon ten thousand amounts of gold or silver (one talent was worth about 6,000 denarii silver, 18,000 denarii gold), this “slave” is more than just some Joe Schmo.

A talent is actually a weight (about 75 lbs.) of precious metal, which can then be smelted into denarii coins, with ten thousand talents being representative of 75,000 pounds of gold and/or silver (roughly $1.56 billion @ today’s price of gold). A king (or emperor, like Augustus Caesar) that “loans” that much wealth, would only do so to a governor (like Pilate, or the sons of Herod the Great), or perhaps whoever was in charge of the seemingly never-ending beautification and remodeling that going on at the second Temple of Jerusalem (Herod’s Temple). Since no small-time “slave” will ever be able to get that deep into debt, let’s pretend Jesus had in mind the High Priest of the Temple as the “one who owed … ten thousand talents” to the king (or emperor).

This would mean that the king (or emperor) was led by God to give or loan that much wealth; but because the “kingdom of heaven” made the king decide to settle up with those who owed him, the “kingdom of heaven” was then like a doctor telling the king he only had so much time left in this world. While love and recognition of God led to his benevolent loans, failure to be repaid with death so near meant the only way to get something back would be to sell the slave and his entire family and possessions.

This would mean changes would be foreseen in the management structure of the king’s empire, like him sending an envoy to an Assyrian king or Persian king, letting them know Galilee and Judea (along with a lovely Temple-Palace) was on the market to the highest bidder. This, of course, would upset the High Priest significantly, causing him to plead with the King (or emperor) not to let heathen take over the building where God lived.

When the slave “fell on his knees before [the king (or emperor)], saying, ‘Have patience with me, and I will pay you everything,’” that was like Peter catching Judas stealing funds for the group surrounding Jesus. Once confronted with being found committing the sin of living off the donations and personal contributions of the disciples and their families, Judas must have begged Peter to not tell anyone … he would repay everything he owed. If Jesus spoke to Judas about his sins, as the king (or emperor) warning how Judas was damning his soul, meaning his own deeds were selling him into the service to Satan and eternity is Hades, then Jesus would have done that individually, before progressing the issue to the whole group. Jesus confronting Judas would have had him pleading for forgiveness, like seen in the parable.

The personality of this slave in the parable shows that his first sin was as a thief; but he then followed that sin closely as being a liar. To have accepted large quantities of gold and silver as loans, when such quantities could only be repaid by a king (or emperor) and never a slave, was stealing. The promise of repayment, both prior to the loans and after payment was demanded, was a lie. Most probably, lies were made to get the loans. So, the slave is like the habitual sinner that Peter asked Jesus, “How often should I forgive a person like this?”

To then hear Jesus say, “Out of pity for him, the lord of that slave released him and forgave him the debt,” this is only done by the king (or emperor) acting as a seventy times [plus] seven. The Greek word “splanchnistheis” has been translated to read, “out of pity,” but it properly says, “having been moved with compassion,” which is more than some slight degree of sympathy or sorrow felt (imagine Bernie Maddoff telling all he owed money to how sorry he was and them releasing him of his debts “out of pity”).

The Greek word “splagchnizomai” (the root) is best read as meaning “to be moved in the inward parts” as feeling “compassion,” which becomes a statement of a higher presence that offers forgiveness. Such deep feelings come from God’s presence, which then offers forgiveness of debt. When Peter suggested seven times, that meant a one-to-one exchange (a 2); but human beings do not get moved by the lies of thieves, when caught red-handed, so a common forgiveness is void of compassion. The forgiveness Peter was referring to was by orders from God, leaving deep-seated residues of resentment. Therefore, Jesus was telling Peter, “You have no powers of forgiveness (as a 2), as only God can forgive sinners.”

It is easier to grasp this as the message when the forgiven slave then reacts to forgiveness like this in the parable:

“But that same slave, as he went out, came upon one of his fellow slaves who owed him a hundred denarii; and seizing him by the throat, he said, ‘Pay what you owe.’ Then his fellow slave fell down and pleaded with him, ‘Have patience with me, and I will pay you.’ But he refused; then he went and threw him into prison until he would pay the debt.”

There is a saying, “A leopard can’t change its spots.”

It actually comes from Jeremiah (13:23), who wrote, “Can an Ethiopian change his skin or a leopard its spots? Neither can you do good who are accustomed to doing evil.” (NIV) Jeremiah wrote that as a response to his writing, “And if you ask yourself, “Why has this happened to me?”– it is because of your many sins that your skirts have been torn off and your body mistreated.” (Jeremiah 13:22) Therefore, the sinful slave, even after God-inspired forgiveness, will still be sinful.

The reason no lasting change will take place is we human beings are born to a sinful world and no matter how much we try to will ourselves to be sinless, we will always have that will broken by the lures of that sinful world. We are therefore 2’s, us (1) in the world (1). It is our dual nature. Only by the elevation of God can we ceases being sinful AND forgive others of their sins against us.

In the parable told by Jesus, we read how other slaves saw what had happened and ran to tell the king. This is symbolic of how those led by God will be enlightened as to the truth that is often covered from them.

It is by being at that elevated state of eleven that we are led to the truth. This is how Peter became aware of those sinning against him and how Jesus knew everything about Judas, well before his final betrayal.

It becomes vital to grasp the change of attitude the king has in the parable, after he has been made aware of his “wicked slave!” We must realize that the forgiving king (or emperor) was led by God to forgive, by feeling compassion from an inner presence. That presence of the LORD has not left the king (or emperor), when he confronts that wicked slave a second time, knowing that the wicked slave has sinned once again against him. We read: “In anger his lord [the king] handed him [the wicked slave] over to be tortured until he would pay his entire debt.”

That is the answer given by Jesus to Peter, about how much forgiveness devout Jews should have in dealing with wicked Jews. Jesus said not to be forgiving simply because you believe in a merciful God, as it is written in Numbers:

[Moses said to the LORD] “In accordance with your great love, forgive the sin of these people, just as you have pardoned them from the time they left Egypt until now.” The LORD replied, “I have forgiven them, as you asked. Nevertheless, as surely as I live and as surely as the glory of the LORD fills the whole earth, not one of those who saw my glory and the signs I performed in Egypt and in the wilderness but who disobeyed me and tested me ten times—not one of them will ever see the land I promised on oath to their ancestors. No one who has treated me with contempt will ever see it.” (14:19-23, NIV)

Only the LORD can truly forgive, although common and mundane believers in God must accept sin in others as a way of the world, forgiving it when confronted and repentance is given by the sinner. Disciples in training must both ask God for forgiveness and “forgive those who trespass against us,” in order to be elevated to Apostles. However, forgiving as a means of forgiving someone else who reflects one’s own sins is not a state of true repentance (“forgive me for my sins like I forgive those who sin like me” misses the point).

This is why this parable ends with Jesus saying, “So my heavenly Father will also do to every one of you, if you do not forgive your brother or sister from your heart.” A disciple is training his or her brain to develop a will to obey the Laws of Moses, but an Apostle has gone beyond the thought process of self-power and fallen in love with God. When one loves the LORD, one opens their heart to receive God in marriage (“till death do us part”). With God in one’s heart, one will be led to forgive a brother or a sister from inner stirrings of compassion and pity. Still, with God in our hearts we will condemn those who are wicked and do not welcome the LORD as their lover.

It must be seen that this lesson in no way contradicts the prior lesson about maintaining the purity of the “Church,” where Jesus explained the process of confrontation that is a devoted believer’s responsibility. The issue of forgiveness is then a subset of confrontation, where we are also responsible for forgiving those who repent, once confronted and exposed as a sinner. At all times, a true Christian will attack the wicked who sin against Christ by saying they are Christian and not acting as such.

A true Christian also has God within him or her, so their ego has been sacrificed for the will of God to shine through him or her. The will of God will tell a true Christian when to show compassion and forgiveness from the heart (an inner part). However, the will of God will equally tell a true Christian when to cast evil out from his or her midst.

The moral of the story, which applied then as it applies today, is to elevate your common and mundane self to a self that is led totally by God. Then you don’t only act Christian on Sundays (day seven). You act Christians 24/7 (or seventy times [plus] seven).